Heard on The LDA Podcast

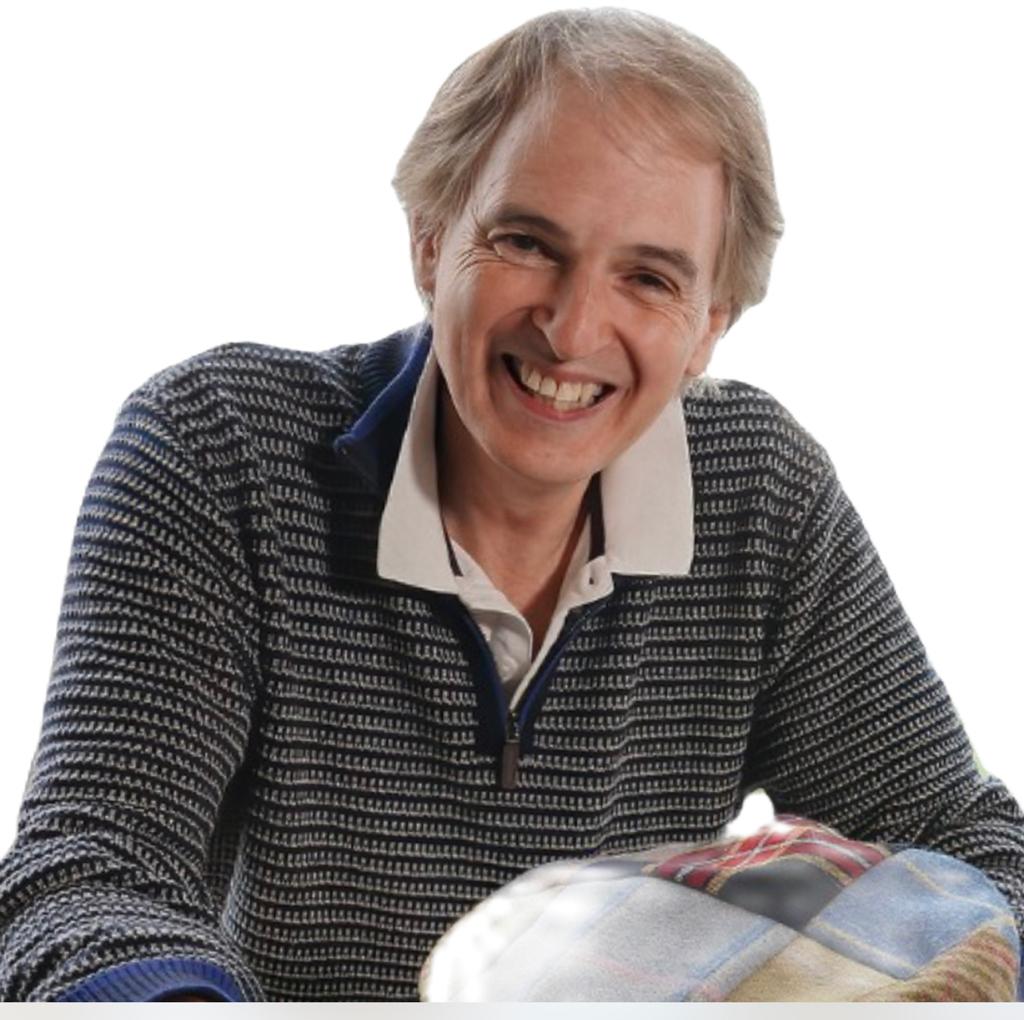

Mark Stoddart, a renowned Scottish sculptor with dyslexia, has dedicated 30 years to creating captivating bronze sculptures. Many of these pieces serve a dual purpose of raising awareness and generating funds for important causes, particularly for neurodiverse education. In this episode, Mark shares his own difficult experience with school, his philanthropic work, and the importance of kindness.

Read the Transcript:

Lauren Clouser, Host:

Welcome to the LDA Podcast, a series by the Learning Disabilities Association of America. Our podcast is dedicated to exploring topics of interest to educators, individuals with learning disabilities, parents, and professionals to work towards our goal of creating a more equitable world.

Dr. Monica McHale-Small:

Hi, everyone. This is Monica McHale Small and I am the director of education for the Learning Disabilities Association of America. And I have the great privilege of being with Mr. Mark Stoddart today. Mark is an artist, philanthropist, and a dyslexic and neurodiverse individual. He’s coming to us today from Scotland. And I had the great pleasure of meeting Mark when I was in Oxford, when we were both in Oxford for the World Literacy Summit. Mark’s story is really fascinating, and I thought that all of you would appreciate hearing a little bit more about Mark Stoddart. Hi, Mark. How are you doing?

Mark Stoddart:

Fine, thank you very much. And thank you for asking me to talk.

Dr. Monica McHale-Small

Well, thank you for saying yes. So I wanted to start with because this is what really fascinated me when I got to meet you. Tell us a little bit about your work, both your work as an artist and the philanthropy that you’re doing in the education world.

Mark Stoddart:

For 30-odd years, I’ve been doing bronze sculptures and also just recently started to do sculptures in silver and also sculptures done in 100% pure Scottish gold. Over the 30 -odd years of doing the sculptures, I’ve tried to give back to numerous charities around the world. From my sculptures, I would donate a piece to help raise awareness and also to help raise funds for different charities. The amount of pieces that I’ve done over the years is quite…well, it surprises me that there is no part of the world that somebody has not collected one of my sculptures.

And last year I was out in the Philippines, and a gentleman, a Scotsman, said, what about the Antarctic? Oh, dear. And I paused for a minute and I thought, oh, dear, somebody might have got me there. And then I thought yes and no. And he’s like, It can’t be a yes, and it can’t be a no. It has to be one or the other. I said, well, it’s not, actually, because there was a ship built in Norway that sailed for the first time round to Southampton. I had to meet the ship at Southampton, and I did a sculpture that went on the ship. The ship is like people’s, huge, big Manhattan apartments, and the ship sails around the world constantly, and the people get on and off the ship and jump on and off to their apartments and quite often on various houses around the world as well. Very fortunate. And the ship had been in the Antarctic. That is somebody’s actual home. So I thought, yes, it has been. And I have supplied to somebody’s home that was in the Antarctic when the ship was and he’s like, that okay. You got me.

Dr. Monica McHale-Small:

Okay. Yeah, that’s pretty cool. I don’t think many artists can have that claim to fame.

Mark Stoddart:

No, I mean, it’s amazing. I did a piece for the man that walked on the moon, I’ve done a piece for Sir Elton John, I’ve done a piece for the King of Saudi Arabia, and the list just goes on and on. So, yes, it’s an extremely fortunate position to find myself in. And through doing all that, I’ve tried to give back to different charities. One, obviously, that is extremely close to my heart is dyslexia charities. And when I lived down in London, I used to help the British Dyslexia Association. And then when I moved up to Scotland, I became an ambassador for Dyslexia Scotland, and I’ve been for quite a lot of years now and done numerous things to try and help them in different ways.

But during lockdown, I mentored somebody through Dyslexia Scotland to do his own sculpture. And I funded it to be done in bronze and 100% Scottish gold. And his sculpture was based on David and Goliath, the kind of fight of dyslexia against the bigger element, the establishment. And I also got it all filmed and done, and also we got it revealed at the Scottish Parliament, where I’ve got one of my sculptures within there and did all the media coverage for them and got it into quite a number of newspapers, magazines, and BBC did a piece on it as well. And then I thought, what else can I do?

Because during lockdown, a lot of people I believed were going to be struggling. And so I paid for quite a number of students, young kids in Indonesia who are dyslexic, and from underprivileged backgrounds, they will earn less than $50 a month, their parents, and bought laptop computers, et cetera. And then I thought, well, what else can I do? So I ended up funding to build the only dyslexic neurodiverse school in Indonesia. And the school is also eco friendly and carbon neutral. The first phase is built and up and running, and we’re building the second phase as we speak. And they’ve got about 135 students at the moment. Some of them are still in their own schools. And the teachers go out, they’re all from underprivileged backgrounds, and the school funds them to go to school and pays for it, and pays for their school uniforms and pays for their school books and for them to be taught.

There is a zoo in America, in Cincinnati, and it had a very special piece. And I thought, what can I do with the piece? And the zoo has a hippo called Fiona the Hippo. So I contacted them and I did a raffle with the zoo for this special sculpture that I have. And we raised about 90,000 with the piece and a small percentage went out to Africa to help build the foundations of the school. There. Again, the only dyslexic neurodiverse school in Kenya. So that kind of got itself up and running and I ended up financing to build the whole first phase of the school personally.

And when I went out in November there, the school organization had been going for ten years, but had zero recognition from the Kenyan government or the education department. And I managed to make contact with them. And one of the education people came along, they loved what they were doing, but sadly condemned the school that they were in. And they said that the classrooms were far too small, the windows too small, doorways too small, the way down to it was not disabled access friendly in any way or anyhow, and the places that they were sleeping in was not fit and where they cooked was not suitable. And if you moved the stones away where the kids played in the middle of the area, it hadn’t rained for two years, but it was soaking wet and it was only coming from one place and that was a septic tank. And so there was a good chance the kids would sadly end up with diseases that could be unimaginable. So they basically condemned it. It was the end of November and that was the kids just that day actually going off on their summer break.

So he says, well, Mark’s actually funding to build a school and we started it January, do you want to come and see the new place and where it’s get done? So the Education Ministry came over to look at it whilst I was there and they were like that, wow, this is something else again. And it’s only Mark that’s funding this. Yes. Okay. The school comes back on the 25th of January. It wasn’t me that picked the date, but it happened to be Rabbie Burns Day, the Scottish poet. And that’s when the school was opening up again and she turned around and said to Nancy, that runs the school, could you get the school, the first phase finished by then? So, of course they both turned around and looked at me. In other words, could you finance it? So, absolutely astonishing.

The contractors that were building the school, as I said, had been building since January. This was the end of November. There’s still a lot to do. They worked every single day up till the 25th of January and took one day off Christmas Day and that was it. They worked flat out. So I turned around and said, one, the school had to be finished and done. But not only that, I think you should have a grand opening day when everybody comes back. And they were like, you’re kidding. And I says yes. And they says, Well, I’ve got the money. I says, I’ll pay for the grand opening because you need to celebrate what you’ve achieved. And a pat on the back, have your friends, your relatives come along because you’re just not going to do it further down the line. It’s not going to happen. We could do it. You’re not going to do it. So they did, and they walked from the old school with their possessions to the new school and then had a big opening.

I managed to get somebody from the ministry to come along of education and do the grand opening. There was a mix up with my visa, so sadly, I didn’t make it out for that occasion. But they read out my speech and they did a grand opening. And I had designed a plaque to go on the wall and they did that. They put a paper version of it on the wall and planted a tree. And the person in the ministry did it all on my behalf. I mean, fantastic job they did. The school very much focuses on the arts. Both schools do. But they also very much focus on trying to give the children an ability to be able to live a happy, normal life and will teach them. The school in Kenya teaches them how to make their own clothes. There’s a farmer there with a bit of ground, shows them how to grow their own crops, and there show various forms of art they’re showing how to do.

But if somebody turned around and said, okay, you’ve given us the hardware, but you also have gone and given us the software because I funded Kate Kate McElderry from the Odyssey School in Maryland to do three zoom calls with the teachers before she flew out to the school in Kenya and did a training course and then do two follow up zoom calls. One was in July and the next one’s going to be in August. But rather than take a training course from the UK or a training course from America and just shoehorn that in, Kate and myself decided to try and tailor make it so people in Africa could identify with it and associate with it. So we introduced the big five animals and we introduced zebra stripes and introduced patterns from, say, materials and patterns from giraffes, et cetera, so they would associate with it. I’m conscious that the school is important and what Nancy and Phyllis that run the school do is important, but that doesn’t touch necessarily the rest of Kenya.

So some of the teachers from schools in very remote parts of Africa, I funded some of them to come to the school and get taught by Kate, and somebody from Botswana came from other parts of Africa, came and sat in in the training course. But I also managed to get three of the education directors from the Kenyan government to also come along. And whilst I was out there, I got an appointment to go and see the Education Minister for Kenya to do with disabilities. And I also managed to see their training facilities for all forms of disabilities throughout Kenya and how they teach teachers.

The school is less to do with dyslexia, but they also have kids that have got cerebral palsy, they’ve got children that also have, say, problems with deafness, mild autistic, et cetera, et cetera. And so they’re all different forms of disabilities they have. And it crisscrosses. The word dyslexia, I think, can be quite a misused word because it crisscrosses over such a spectrum and what the government saw there and has been done, they absolutely love it. And we’re asking, is it possible to create a training manual book of some description and could they introduce that into their teaching and roll that out throughout Kenya? Four teachers that I paid to come along from a very remote part of Kenya, it’s so easy in life that you could go back to your normal way of doing things and just say, yeah, that was interesting, but let’s just stick to what we know. Oh, no, they have not done that. They have done the total and absolute opposite. They managed to get one of the schools that they work in to put a classroom aside, and in the first week, identified about 36 dyslexic children. They’ve identified more since another school nearby has allocated a room, but it needs renovated, it’s quite primitive, and I’ve offered to help pay for that.

And they’re looking at another school. And just on Friday there, they contacted me to say that the Ministry of Education for Kenya had paid them a visit and they had gone and looked at it, and I said, yes, I knew about it. I requested through somebody in Kenya, Anne, who works for the Worldwide Rotary Club for Disabilities, and she’s been helping me and she worked for the government. She got the government to go along and do it and they, ah, we now understand why they paid us a visit and why they were so interested in what we were doing and insisted that they saw this classroom and the training materials that we’re using that you had given us. And they want us now to go out into the very remote villages and identify dyslexic people and bring them into the classroom and start to teach them and to accelerate what we’re doing. I am absolutely blown away by that, that they could have so easily just gotten about it and just done and got on with our way. They do things normally, the total and absolute opposite. And I just find it astonishing what they’re doing.

Dr. Monica McHale-Small:

As you’re telling me all of this and going through all this. I think what’s happening, Mark, is that your incredible generosity is really inspiring other people, right? The people who were building…how many, how often does that happen? That a bunch of workers just decide, yeah, we’re not going to stop until it’s done? And I think that’s really reflecting back on you. You are inspiring others to go above and beyond the way that you are going above and beyond. And I started making little check marks on the page, but I lost track of all the people that it seems like you’re touching and then they turn around and spread that generosity, that compassion, that desire to change the world for better. So I think people are now understanding why I was so anxious to have you on this podcast because you’re certainly inspiring me, so I thank you for that. Do you ever sit back and just think about that? How many people you are touching and how many people they are now touching and how much you’ve already changed the world?

Mark Stoddart:

I’ll turn around and say something and people will find it bizarre. It was years and years ago. On an occasion I met Sir Jackie Stewart and I said something to him and he paused and I thought, oh dear, I’m not going to get a good reply to this. And he replied, then I said the same to him. And I said, I spoke to you a few years ago and I said that despite all the things I’ve done for different charities throughout the years, and despite all the different things I’ve done through my art, I’ve been massively privileged to meet a lot of very interesting people through my art. And I did a piece out in South Africa, and it was for Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s charity for kids suffering from HIV. And it had just come about at the time and it was part of the South African government inviting me out. And I’d done a special piece for them to raise money, et cetera. And I said to him, I said, despite everything I’ve done that I don’t feel I’ve ticked the box and I don’t feel as though I’ve accomplished anything.

And he turned around and said to me, I’m the same. And I found that to be astonishing. And he says, if you sit and think about it, that we both are the same and that is probably why we carry on doing what we do, that we haven’t done it. And if we had, we probably wouldn’t carry on doing what we’ve done. And I thought that’s probably a very wise way of looking at it. I mean, don’t get me wrong, I’m massively privileged and I’m massively grateful for what I’ve achieved and that I am in a position that I can afford to finance personally and build these schools and do what I’m doing. And on the back of it I’m getting asked to do various talks to different places all around Africa.

And when I was out just last month, I went out with Kate Kate McElderry and we did a book talk and I met a friend in Dublin who he’s built eleven schools through a charity himself and two other people set up in 2006 and it’s eleven schools for underprivileged children in India. And he’s asking, could I please help him? Not my money, but could I help him identify somewhere. I know people in India and Delhi to build a school for dyslexic neurodiverse kids and could I help him in some way identify dyslexic neurodiverse children in these eleven schools? I mean, one of these schools has 1000 kids in them. That’s quite astonishing. So it’s quite mind blowing what’s getting done.

But as I turn around and say absolutely none of this is about me and when we did the grand opening of the school in Kenya and then did it in the one out in Indonesia, I said it’s not about me, it’s not about people who also running it and setting it up with me that do the day to day running and organizing it. And I said it’s not about the teachers, it is totally and absolutely about the children that we’re all doing this for you and for you to hopefully give you the tools and ability to realize your own personal dreams in life. And that is what it’s all about. It’s not about us.

Dr. Monica McHale-Small:

Right? I think that’s a great segue into you and talking a little bit about growing up and your experiences in school because I’m guessing that part of what you experienced is part of what drives the work that you’re doing now. Could be wrong, but you shared a little bit with me when we were in Oxford, so maybe tell us a little bit about your experience when you were in school. What happened?

Mark Stoddart:

Sadly, I didn’t…well, the early part of my schooling was not very happy and it was different times back then and this is the same with what’s happening out in Africa, it’s different times. And there was, say when I was about a six, seven year old, I got my sums right. And so the school said, fine, you can have a half day off. And then when I went to the school assembly the next day they said if Mark gets his sums right, the whole school can have a day off. And needless to say, I never got my sums right. I very rarely did. And they decided to make a big white cone and put a D on it and put me in front of the school assembly and then put me in front of the class for a whole day. They thought I was lazy, I was thick, I was stupid and just trying to shock me out of it was the way they went about.

I didn’t know I was dyslexic or neurodiverse or dyspraxic and so on. And so I got quite heavily bullied, and that’s from the kids, the teachers, the headmistress, and then the other school headmaster and the other school I went to again when I was held back in the classes and there was quite a few things happened to me that should never happen to children. And it was all to do with being dyslexic. And I would always be the last person to be picked to play in football or any eye-ball contact or even gym for coordination. And there was a teacher that I had out with and she would leave me standing for 45 minutes trying to just get the one word and it’d be a double barreled word and I just couldn’t put it together, I just couldn’t get it.

My parents had a lady that lived a couple of doors down from us and she was a retired headmistress and she used to try and give me some extra lessons, but I still, as I say, struggled and didn’t know I was dyslexic, but the school I was at was a prep school and you leave about 13, 14. And I went down to a school in Wales for an interview and the headmaster there interviewed me and then said to my father, no, your son’s not daft, thick and stupid. This school is totally the wrong school for him. The school could have skimmed across the three R’s to what legally they could get away with, but really looked at car mechanics, farming and swimming and everything else but arithmetic and reading and writing. And I’d got into stamps back then and the chap happened to know about it and said, no, your son knows all about this. And says, no, I actually think he’s dyslexic. So I turned around and said to my father about it, and so my father said to the headmaster of the school that he had been there. And they think, Nah, there’s no such thing. Nah, no, and did nothing. So, in the summer term, my father, through a friend, got a child psychologist to come and test me and says, oh, gosh, no, quite straightforward. Your son’s dyslexic and the school he’s going to is doing massive amounts of damage. You cannot send them back there.

So I never went back, so I never saw any of my friends. And at that point I’d gone into a shell. I wouldn’t go on a bus, I wouldn’t go anywhere, I wouldn’t talk to anybody, I wouldn’t do anything because I thought I was thick, I was stupid, I was daft, and I believed I was a massive embarrassment to the family. And I kept quiet about a lot of things that had happened to me at school and the way I’d been treated. So I was meant to go to a school in Edinburgh, but they had over promised, they didn’t have a space, they had only six dyslexic people there and they weren’t going to take any more. And then my father took ill for two years. I ended up getting left at home and 100% forgotten about whilst my father was ill. And so I just went into gardening and just bottled about myself and my dog and that was it for two years.

And then when my father, amazingly, got better again against all odds, he took me along to the local council and thought there’s maybe a little outside chance he might get a job, been able to cut grass for the council and do something like that. And that would be the maximum he would ever be able to achieve in his life. And my mother says, you can’t do that to the guy. You’ve got to give him a chance in life. And so she reported them to the authorities that I had never been at school, and there were no teachers, and I wasn’t getting taught or anything. So my father put his big effort into it and found a school down in Sussex. And I’d never been away from home or anything, and the school was the first dyslexic school in the world, and the school has been going for way over 100 years. And at the time, the school was the second most expensive school in Britain.

And I was fortunate to have the parents that I had in some aspects, but in a lot of other aspects, probably not. My father was very successful and very overpowering and just couldn’t really see why I wasn’t doing and wasn’t able to do what I was doing and was an embarrassment, probably. And my mother, yeah, it’s a whole other story. And so I ended up going down there and realizing that that was my only chance in life. And school totally changed my life and the way things were. I had to go back to my times table, my alphabet and everything to scratch. And I had about just slightly over two years at the school until I was just over 18. But one of the biggest things the school gave was self belief and confidence.

The headmaster was an absolute character. He had been at Eaton, and then just before he retired, he went back to Eaton. And he had no interest in the parents, but he had a huge interest in the well being of his students. And he would give you as much leeway as possible and allowed me to build self belief and confidence and go up to London for the weekend and go down to Hastings and go to things on a Saturday or whatever and do things. And it just allowed me to find myself, and it totally changed my life, basically, by having that opportunity to go somewhere like that.

Dr. Monica McHale-Small:

That is quite a story. How often do you think about your own experience when you are with the children that you’re helping when you’re working with the schools? Is that something that is always in the back of your mind, trying to find a way for the kids that will go to the schools that you’re involved with to kind of experience what you experienced in those last couple of years?

Mark Stoddart:

If I can put it a different way. I was asked to do a presentation at the end of June there, and it’s an organization called the Sun Books, and they’re the people that organized the World Literacy Summit that we met at. And the CEO of that is actually based in Melbourne in Australia, and it turns out that his ancestors came from Glasgow and owned a ship building company in the Clyde. And they asked me to do a talk and it’s to teachers all round about Africa and some of them were asking me questions at the end and I kind of looked at it and thought they were wanting me to explain about dyslexia.

And I said, I’m not a teacher, I’m not an education person, so I’m not going to wade into it. I said, yes, you can identify a dyslexic person. They can be somebody very quiet in your classroom. It can be somebody that’s the joker in the classroom, it can be somebody that’s disruptive in the classroom and it can be somebody and they said, well, what about cat and dog and B’s and D’s? I said, yeah, we can go into all that, but I said, I’m not a teacher in education so I won’t do that. But I said the one thing that I can do is turn around and say to you, Be kind.

I says, I can’t give you the tools to then if you identify and I’m not doing that at this stage, but we’ve got another meeting where we’re bringing a specialist in that’s going to tell them this Friday coming, so we’re doing it again because they’re just so fascinated by it all. But I said, be kind, and I know sadly, how some of them in Africa do treat people like that. And I was like, Well, I can’t wait in and start saying any of this, but I said, Be kind, and they said, yeah, we give them names or whatever. I said, don’t do it. I said, please be kind.

I said, because if I go back to myself, I said, what I got put through and what happened to me imprinted in my life and it still stays with me for the rest of my life. And I said if I ever hit a little bump in the road, all these voices, all these people that turned around and told me that I was thick, I was stupid, I’ll make nothing in life, I’ll not achieve it in my life. It still comes back and it’ll still haunt me and people say, but that’s not possible with everything you’ve done and everything you’re doing. I said, It still does.

I still at points, it can just suddenly hit me where I get panic attacks and anxiety attacks. And especially if I’m somewhere around the world, it can be in the middle of the night. I could semi-waking up. And my partner usually comes with me because I can be kind of frightened and I shouldn’t be. But my whole life suddenly focuses on a pinhead and I feel terrified and I just feel that I want to go home. I have nothing to go home back to. There’s no rhyme or reason why I should want to go home because there’s nothing there to go back to, go back to. And it all stems from what I was put through.

And so what I turned around and said to them is, please be kind. And so what I’m doing with the schools and trying to do is give other children an opportunity to realize their own dreams and so on, but more importantly, not hopefully go through what I went through and be put through what I was put through, because it imprints, and it can imprint the rest of your life. And people, possibly just ignorant, don’t realize the way they treat somebody when they’re very young and what they do to them can actually have a massive effect.

As I turned around and I said to the Kenyan Minister for Education, I said, I have no statistics for the UK. And I’ve no statistics for Kenya or other parts of Africa. But I believe America has done statistics that 75% of prisoners in prison have a very low reading age and I believe can also be dyslexic neurodiverse. And it all spins out from that to where you end up with mental health issues and everything else and so on, that if you just get to a point where somebody lives a happy, normal life and is not a burden in their community and their country, you’ve won.

Dr. Monica McHale-Small:

Right? Absolutely. Yeah. And I think we forget there’s no better advice, I think, in the world. Just imagine what our world would be if everybody just was kind to everyone else. It would transform the world. But I think, too, what you’re saying is so true that children spend most of their days, most of the hours of the day in school. And that experience is really shaping how they will feel about themselves for the rest of their lives. And they really judge their own self worth in comparison to their peers. And if they’re not right where their peers are, they can be very hard on themselves. So I really appreciate what you’re doing and your advice about being kind. I agree. And I worked in public schools, and that was something whenever I was hiring people, that’s really what I was looking for. Right. You can teach teachers the skills to improve their practice, but you can’t take an unkind person, necessarily and make them kind. So I was always looking for somebody who I felt was going to treat children with respect and kindness, because I think that might be the most important thing.

Mark Stoddart:

Well there’s quite an interesting sorry, if you go back to the word kind, there’s a movement called the Kindness Organization. And last month, I met a gentleman. He’d come over from Bangladesh. He’s a doctor, but he’s stopped practicing to run this organization, and his wife’s a professor. And it’s the kindness movement. And he’s looking and interviewing people for the hundredth most kind people in the last 20th century, and he very kindly interviewed me.

Dr. Monica McHale-Small:

I would bet that you’re going to be on the list because that is one of the things that really struck me about you. So I do have one more question, actually. I could probably talk to you all day because I’m so inspired by your story and by what you’re doing in the world. But I don’t know if you remember when we were in the pub, which is where we met and in between sessions and we were talking about the idea that what I find is when I speak to adults with learning disabilities is that they’ve often have found the workaround.

I think a lot of educators think, okay, we teach them to read and write and do arithmetic. Problem solved, right? But when I talk to adults, they have found the workarounds for their areas of weakness, whether it be reading or writing or arithmetic. They find a career path or a job that’s not going to put a lot of demands on where they’re weak or maybe they’re using technology tools to kind of work around. But when they talk about how their learning disability or dyslexia or neurodiversity continues to impact them, they talk about other processing deficits. And you and I spoke about that, and I’m wondering if you could talk a little bit about what’s hanging on in your life as an adult as far as your learning disability and how do you see it continuing to affect how you function in the world.

Mark Stoddart:

Big question, to say the least. There’s quite a number of people around the world trying to do things for dyslexia and neurodiverse, people that I think are absolutely fantastic in creating awareness about it, and especially with adults as well. There are some people saying that every dyslexic person has a superpower. Well, that brings its own complications. I mean, even out in the middle of nowhere in Africa, they are getting a backlash from the parents turning around and saying that my child has got a superpower. Why are you not finding the superpower? And you’re like, not everybody has got a superpower. And even if they have, do they want to be the next Henry T. Ford and so on? No, it brings a lot of its own pressures.

So you kind of learn more and more about dyslexia. And as I say, it’s a misused word. There’s so many different crossovers with it. And I could sit at a dining room table and there’s quite a number of friends, and there’s, say, one person like my partner, and she can be chatting away and I’m talking to somebody next to me that I don’t know. I will only be getting about two words and one word to the person I’m sitting right next to talking to because my brain is pulling in the conversation to somebody that I know. And it’s the same thing. She’ll be on the laptop doing away and I’ll have the phone, the television going, and I say, you’re wasting your time, you might as well talk to the wall. I cannot pick it up. My brain will be tuning into something on the television, picking a word up, you’re saying, then pulling in from there. And I’m not getting it, that what I’ve done is as much as possible, recognize my strengths and more importantly, recognize my weaknesses.

I play to my strengths and I work out ways to shore up my weaknesses. But Maggie in my office is an absolute lifesaver and she very much shores up all my weaknesses. And believe me, there are plenty and that allows me to function the way I do. I fully understand a lot of adults in various jobs. They will do a job that will take them to a point that means they don’t have to go and face their weaknesses. And more importantly, a lot of people will hide their weaknesses because they worry that it will threaten their job or their job prospects and so on and try to stay away from things like that.

I had it when I worked for different companies way back when I was engaged, and there was a chap, Gavin Hastings, who was a very good rugby player and he worked for a big insurance company and they offered me the job when he decided he was given the job up. And they said, you’ve got the right image, the right look and presentation, job is yours. And then they say this is very weird, but the chap in charge has asked you to go up to the boardroom and never does, that’s weird. I went up, sat in the office, chatted away to him for a little while, then he got a newspaper, shoved it under my nose and said, I believe you got something called dyslexia. Could you read that sentence there?

And of course, the worst thing for dyslexic is to be put under pressure. You start just going haywire. And so I kind of stumbled over it and he says, oh no. He says, we couldn’t employ somebody like you. Oh no, we couldn’t have somebody like you working for us. I said, But I’ve been offered the no, no, I’m taking the job. Sorry. No, definitely it impacted my life and ended up not saying just because of that, but ended up I was getting a house built in Walton Thames down in Surrey and we had the church built and everything else and I ended up losing the relationship, broke down and so on. And yeah, it could have impacted on my health.

So if we can revert back to the word kind that I understand, that people don’t understand and don’t probably kind of relate to it, but don’t put somebody down because of it and don’t do it. If you look at, say, somewhere like NASA, NASA has, what, I think it’s 60% of people who are dyslexic neurodiverse working for them? Why? They see things differently. They look at things differently. And if you can have a dyslexic neurodiverse person working for your company, you can be sitting on a boardroom table and everybody’s sitting, chatting away. They will just go put the finger straight on it. And everybody’s like, how did they see that? They see things differently. They look at things differently. They see it in a different way. They can be a massive, massive help and advantage to a company. So realize what you’ve actually got and it can be a massive thing to have somebody like that working for you.

Dr. Monica McHale-Small:

Absolutely. And unfortunately, the Learning Disabilities Association is often contacted by young adults out there in the workforce having negative experiences like what you described. And hopefully, as we build awareness and we highlight people like you, Mark, who have achieved at such high levels, maybe people’s perceptions will change and more people will give people who are neurodiverse a chance. So thanks for talking with me today. It’s been really interesting and I can’t wait to talk to you again with your co-author, Kate, who you’ve mentioned several times, hoping that we will get to talk about the book that you and Kate have coming out in October or the end of September. So thank you very much and have a great day.

Mark Stoddart:

It’s been an honor and thank you very much for asking me. And hopefully somebody gets something out of what I’ve been talking about.

Dr. Monica McHale-Small:

I think a lot of people are going to get a lot out of your story. So thank you.

Lauren Clouser:

Thank you for listening to the LDA Podcast. To learn more about LDA and to get value, resources and support, visit ldamerica.org.