A Q&A with Gregg French, special education teacher at Bullard Havens Technical High School and president of LDA Connecticut

Accommodations and Strategies

What are some accommodations and teaching strategies that can be used in a general education classroom to help students with learning disabilities?

I spent a lot of my teaching career focusing on differentiation of instruction, and how beneficial that is to not only students with IEPs and 504s, but students who are below grade level or at risk, and for students that are primarily non-English language speakers. So differentiating instruction is beneficial for many different types of students that we encounter in our classrooms.

What is differentiation of instruction?

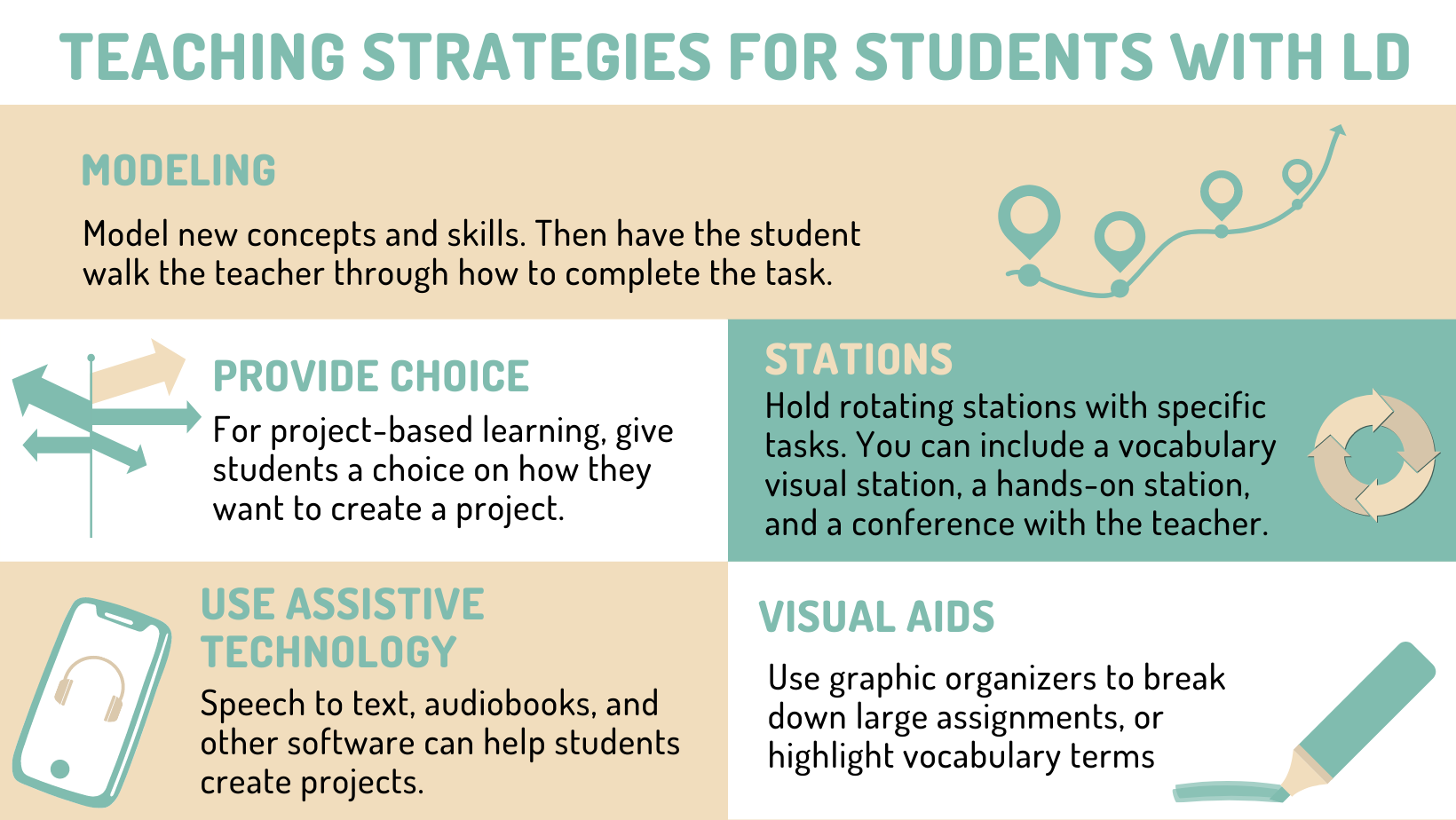

Differentiation of instruction is a teaching model that looks at explicitly teaching content in different ways. One of the strategies that I find very much used in my school is the gradual release of responsibility. I see a lot of teachers modeling new concepts and skills, and then teachers provide guided practice where students, once a teacher feels that they’ve modeled enough, have the students walk the teacher through how to complete a task, or do an assignment. And then based on the guided practice and working together, talking it out, the teacher can get a sense of, ‘okay, I feel that this group of students can do it independently, go for it. Maybe this group of students need to be a little bit more supported with more guided practice or with modeling.’

I’ve seen teachers do rotating stations where there’s a specific task at each station for an allotted time. And it might have a vocabulary visual station, a hands-on station, and a conference with the teacher, so you’re kind of using a wide variety of different approaches to delivery of instruction, teaching and learning.

A lot of teachers I know use project-based learning, and giving students a choice on how they want to create a project is great.

Use students’ strengths to demonstrate and apply a specific skill. I’ve seen teachers who use a lot of assistive technology, speech to text, and audio books. I’ve worked with students in looking at different software to create projects, virtually and digitally. I think COVID virtual learning allowed teachers to experiment with more digital programs and software that can be beneficial to students with LD or without a disability.

A lot of those accommodations that we look for in implementing the IEP can be beneficial for students who are not receiving special education services. Being a visual learner is something that I think each person enjoys, so using graphic organizers to break down large reading or writing assignments can be helpful for a student who’s learning English for the first time, or students that just need that visual support.

Highlighting vocabulary terms and pre-teaching content specific vocabulary can be beneficial to many diverse learners, not just specifically students with learning disabilities.

I make the point to tell teachers that an accommodation you might see in an IEP can become a class-wide accommodation if you feel it benefits all of your students, because I think that’s just part of good teaching.

Partnering with Special Education Teachers

How can general education teachers and special education teachers partner to benefit students with LD?

I really think that one of the most crucial pieces to supporting any student with a disability is the collaboration between the special education teacher and the general education teacher, because there may be a point where co-teaching needs to be embedded in the delivery of instruction, and so making sure that teachers have the opportunity to collaborate, and co-plan, co-teach and co-assess, and come up with a model that fits the classroom.

Working on building positive relationships between both teachers is very crucial, that line of communication needs to be consistent and clear. And both need to understand the roles in supporting the student.

It shouldn’t be me versus them, it should be us working together to support the needs of the student. And so in the classroom, whenever I push in, I always let the teacher lead the classroom. With the delivery of instruction, I will float around and support all students. And I think that’s really key.

Students who have IEPs and a learning disability don’t want to be picked out in the crowd and have an adult hovering over them. I see my role in the classroom as supporting all the students, so I build relationships with all the students. I’ll spend time working with students that aren’t on my caseload, because I know that kids on my caseload are working independently and are perfectly fine.

So the classroom kind of sees me as a co-teacher that’s there for everyone. I don’t hover over a particular student, and that classroom climate and environment is positive. They see myself and the general education teacher as partners, as a resource to ask for help. I never would turn away a student asking for help.

I think it’s also important that the co-teachers use common language and are on the same page of knowing that, ‘Yes, I have five or six students in your classroom that have IEPs that are on my caseload that I’m supporting, but I’m also supporting the entire class’

Advocating for Students

If a teacher has a student with LD and they feel like their needs aren’t being met, how can they advocate?

I think that goes back to the collaboration piece. When a special education teacher is not present in a classroom with a group of students who have a learning disability, and the general education teacher may be struggling with reaching those students or teaching a specific lesson, that’s where collaboration and communication need to come into play.

Having that open line of communication, where the general education teacher is comfortable to say, ‘Hey, I did this lesson today, it didn’t work out for the students, what can I do differently next time?’ Or, ‘Can you come in and maybe I’ll reteach those students and you work with the other group of students and then we’ll kind of do a split classroom.’

No teacher should feel that their hands are tied. And again, I think that goes to building positive relationships, communication, collaboration, and making sure that the special education teacher is also there to support the teacher. Because ultimately, the general education teacher spends the most time with their students.

Advice for General Education Teachers

Do you have any other advice for general education teachers who have students with learning disabilities in their class?

For teachers that find they have a large group of students primarily with LD, the number one thing is to reflect on your teaching practices. Because oftentimes, a lot of students with LD need things taught in a specific way that’s really broken down, through scaffolding or chunking, and usually need a lot of visual supports.

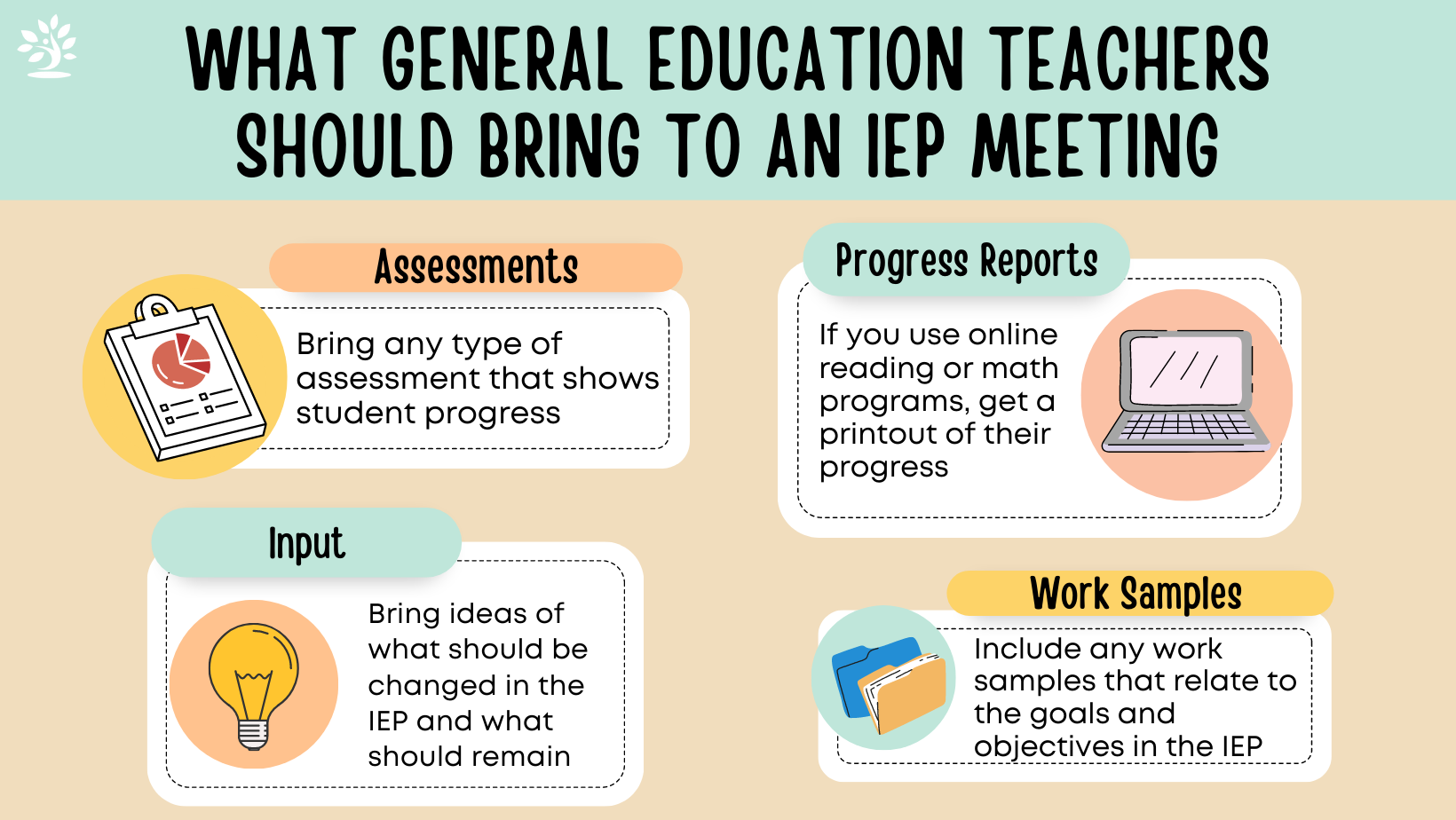

So if you really implement differentiation of instruction, you build strong relationships with those students, you refer to those IEPs, you’re an active collaborative member of the IEP team, and have a partnership with the special education teacher, you’re pretty much meeting all the needs and requirements of effectively teaching students with a learning disability.

And also understand that a learning disability should not be the focus. We want to focus more on the abilities and the strengths of the students. Oftentimes teachers will say, ‘Well, they have a reading disability, I’m never going to catch them up to reading at grade level.’ Well, maybe that’s not the goal, maybe the goal is to focus on what their strengths are, and using those to teach those areas of difficulty. And so it’s flipping the equation, in not so much focusing on the dyslexia, the LD, the ADHD, but focusing on what the student is capable of.

And that’s something to speak to on a personal level. I was diagnosed with a reading comprehension disability as well as a math disability in the fourth grade. And I received special education services throughout elementary school, throughout middle school, and up until junior year of high school. And I remember what it was like, being a student who receives services and had a co-teacher in the classroom, and feeling the stigma of having an IEP, having someone follow you and try to help you. And so my other word of advice would be it’s okay to let the students be independent, because in the end, special education shouldn’t be a life sentence.

And that’s something I always try to tell parents too. I don’t think it is talked about enough, but special education is there to support the student as much as is needed and appropriately. But if a student does find strategies that are effective and is compensating for those areas of difficulty, and they’re doing well academically and socially, students can be exited from special education.

A student with a learning disability will have it their whole life, but can find strategies to really address the difficulties that they’re having academically in school, and we shouldn’t look at them any differently than any other student. And so I think really understanding where the student is and where they’re coming from and building that relationship is crucial.

Listen to the full interview with Gregg French on The LDA Podcast: An Educator’s Guide to Helping Students with LD, Part Two