by Jim Franklin

Jim Franklin is an inclusion special education teacher from Elm Street Elementary in Rome, GA. Jim presented a session at the LDA Annual Conference in Atlanta and submitted this article to share a resource with the LDA Community after reading LDA Today last summer.

Jim’s session focused on teaching the number line to 10,000,000, fractions, decimals, elapsed time, weight, capacity, and money. Jim had developed a new type of manipulative to teach these concepts after he was looking for new ways to work with rounding whole numbers. Jim created a rounding tool based on the number line that incorporated movable, interchangeable slides. After further development and use with students, he was able to further adapt then for use with low vision and some blind students.

Not only did Jim explore his own perceptions of math instruction, but he allowed his students’ experiences and suggestions to transform his perception of what was possible for teaching abstract concepts like rounding, elapsed time, and money. In his article, Jim also shares his experience with a teacher who is an inspiration herself!

For more than 20 years, I have had the opportunity to work with many students who have had one of more disabilities that impede their learning. At the beginning of the 2011-2012 school year, my assistant special education director asked to bring an administrator from a regional education service center to observe my 4th grade math inclusion class. I welcomed the upcoming visit but wondered if any new strategies and interventions had been successfully implemented by other teachers with the concept of rounding whole numbers. I asked other math teachers in my school and searched for ideas on the Internet. Honestly, there were not a whole lot of options. Over the years, I have attended numerous math workshops. I only saw methods that involve number lines, dry erase markers and boards, and blocks. Other than those options, paper and pencil were the last resort. The last thing I wanted my visitors to observe were towers being built out of blocks or off-task drawings on dry erase boards. I could not use the number line in my classroom because it only went to 100; my class was working with numbers greater than 100. Although all four options have been used for years and have had some success, I wanted math manipulatives that could make an immediate impact on educational performance and not be considered a “toy” by my students. Then, I had an idea…

Creating Manipulatives

By incorporating movable, interchangeable slides, I created a number line system that can round whole numbers up to 10,000,000 by using the base-10 number system. It can round numbers to the nearest 10, 100, 1,000, 10,000, 100,000, and 1,000,000. When I began to show this concept to my colleagues, their response was overwhelmingly positive! Teachers began to ask me to help create manipulatives to address other mathematical standards. Eventually, I developed manipulatives that involved weight, capacity, elapsed time, decimals, money, and fractions. During this process, I consulted with math teachers and specialists, administrators, parents, and students from several different schools and school systems. I also consulted with an occupational therapist, a hearing specialist, and vision-impaired specialist. Of all of the stakeholders with whom I worked throughout the initial part of the developmental process, I most valued the student input. After all, they would be the ones who would use these manipulatives as a vital part of their classroom instruction. Because I believe all students can learn, I was able to make some manipulatives available for blind students and all of them for low vision students.

Transforming Perceptions

In June 2013, I was demonstrating my low vision and braille manipulatives at the 2013 Georgia Sensory Assistance Project Conference in Cave Spring, GA. At the beginning of the conference, two women approached my exhibit booth. One woman led the other by the elbow. I greeted them and asked why they were attending the conference and where they lived. I immediately recognized that one of the women was deafblind because of their communication techniques. The deafblind woman, Dana Tarter, was a high school resource teacher in the school system next to mine. Barbara was her intervenor who interpreted what I was saying on Dana’s hand.

Dana informed me that she was at the conference to find assistive technology to help her address and teach academic standards such as elapsed time and money. With the help of Dana’s intervenor, I demonstrated some of my braille manipulatives to her, hoping that I could help at least one of her students. At first I was unsure about HOW to explain my manipulatives because I have never worked with a teacher or student who is deafblind.

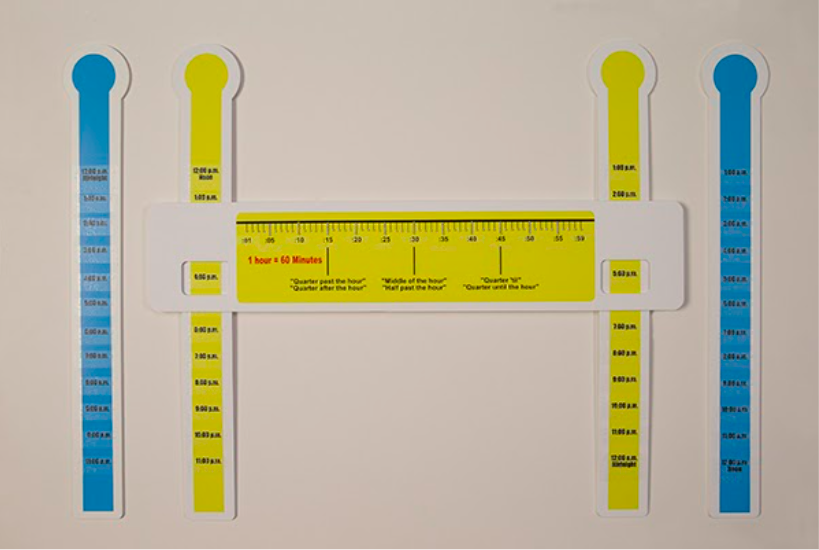

I began to explain the general shape and size of my Elapsed TIme manipulative, stressing how the slides move up and down for each hour, and the tactile dots are used for students to count by minutes. I also mentioned that all of the numeric intervals of 5 were brailled as well as the hours on the slides. Students are encouraged to set the hourly increments first and then count the dots to find the minutes. I noted that more advanced blind students read the braille hour and minute increments of five first and then count the dots, such as for the time 4:38 (4:00 in the left window and 5:00 in the right window then read the braille to :35 + 3 tactile dots equals 4:38.)

During our conversation, we agreed that demonstrating the ability to calculate elapsed time is a complex skill because it involves addition and subtraction that could require regrouping, especially in real-life situations. During the instructional process to achieve mastery, teachers often use the manipulative I developed during the initial part of instruction and then gradually fade the manipulative as the student becomes more proficient. Eventually the students use the manipulative to assess their own understanding. “In other words, students can be held accountable for their work because they have to check their answers themselves. That will allow me more time to help my struggling students”, Dana observed.

Dana gently extended her fingers and then reached towards the 24″ braille Elapsed Time manipulative that had tactile dots. Through Barbara’s interpreting, I patiently explained how the slides represent hourly increments and the minutes were in between the hours on a horizontal line on the main piece. I added that one tactile dot equals one minute and all five minute increments have five vertical dots. Dana, who was fairly fluent in braille at the time, initially began to read the braille labels on the slides. She quickly grasped the design concept because she used self-discovery to learn how to use the manipulatives. The longer Dana used the manipulative, the less Barbara had to communicate. Dana definitely showed the teacher in her because she had begun to create math problems to solve herself. At first, she was somewhat hesitant when she gave her answers, but after trying 2-3 self- created math problems, she stated her answers with confidence.

Dana seemed satisfied with the design concept and instructional potential of the elapsed time manipulative, especially since there were smaller versions for her students to use while she taught with the braille version in a small group.

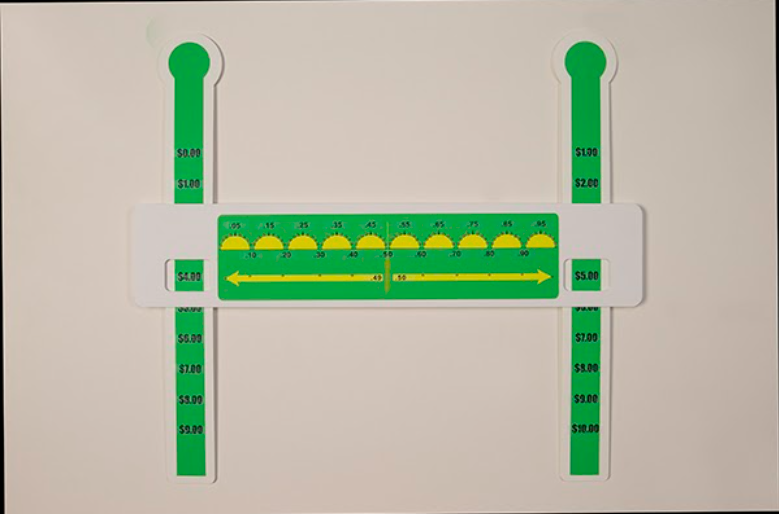

Dana also focuses on teaching math life skills to students in a special education resource room so I demonstrated my braille money manipulative. The money manipulative is the same size and shape as the one for elapsed time. The whole dollars are on the slides and increments of $0.05 and $0.10 are in braille on the main part. Tactile dots are placed on each cent for counting, for adding and subtracting money to find correct change, and for rounding to the nearest dollar. Eventually I stopped explaining and Barbara did not need to interpret any longer. We watched as Dana learned how the manipulative worked through self-discovery. Dana carefully touched the braille with her fingers, with her body leaning over the table and her head about six inches above the slide on the left, orally reading the braille numbers. Her fingers continued to slide across the braille on the main piece, while “whisper” counting by five cents and then by 10 cents until she touched the next dollar on the right slide. She did not expect a full explanation in how the manipulative is used. As a matter of fact, when I began to discuss how the manipulative can help the students add and subtract with regrouping, Barbara looked at me with a smile and quietly laughed, “Just let her do her thing. This is who she is, and she will eventually figure it out.”

While she was reading the braille, she noticed a raised line in the middle. She kept running her fingers across the line and mentioned, “This raised line in the middle….is here for students when they need to round to the nearest dollar. If the amount is on the right side of the line, the students round up to the closest dollar. If the amount is on the left side of the line, students round down to the closest dollar.”

I told her that idea was from one of my inclusion SLD students, Haley. During the design process, when I gave her the money prototype to use in class, Haley quietly asked, “Can I draw a line in the middle (on the label) so that I know which way to go?” Dana, like other students and teachers who use the manipulatives, quickly notice that the proximity of their fingers to the windows on the left of the line in the middle determines which way to round numbers. Because of this intelligent observation from my SLD student, arrows were added to the label that point to the window with the correct answer.

Transforming Instruction

After I demonstrated my manipulatives to her, Dana expressed interest in using them in her classroom because they would provide new strategies to teach difficult academic standards to her students. Dana and I exchanged emails and coordinated our schedules for me to observe a lesson in her classroom.

I arrived during Dana’s planning time and we were able to discuss the manipulatives in greater detail than we had at the conference. Dana’s classroom arrangement included several tables for small group instruction for some lessons, mainly used for individual instruction because many of her students were at different academic levels, especially in math.

During the money lesson, even though Dana is blind, she could visualize how the manipulative would be used by her student. She knew that there was an important line in the middle, semi circles with $0.01 increments on the main piece, and she began to solve math problems by establishing the correct dollar increments in the windows. With the braille manipulative and assistance from her intervenor, Dana provided quality individualized instruction to address her student’s academic goals and objectives with the 11” regular student version. Even though the student had cognitive challenges, he quickly understood the simple steps in finding the correct answer for rounding to the nearest dollar: establish the dollar increments on the slides in the windows; count the lines on the semi-circle; determine if your finger is on the right or left side of the line in the middle. Then, he could follow the arrow with $0.49 or less or $.0.50 or greater to see if his finger was closer to the window on the left or right to find the correct answer.

My observation lasted about 20 minutes due to the need for instruction in other important areas. I sincerely enjoyed visiting Dana’s well-structured classroom. I could hear the positive tone in her voice and quality questions she asked regarding how to use her manipulatives most effectively. This observation was more than watching a teacher use math manipulatives in a lesson; it was observing a dedicated teacher overcome adversity to help cognitively-challenged students learn essential life skills.

Jim Franklin is an inclusion special education teacher from Elm Street Elementary in Rome, GA.

** Please note: LDA America does not endorse specific products. We appreciate Jim sharing his resource and his story for other teachers and/or parents. For additional information, Jim can be contacted through Slide-A-Round@comcast.net.

********************************

Do you have a resource to share related to research, education, advocacy or public policy related to transforming perceptions for individuals with learning disabilities? We’d love to hear from you: editor@ldaamerica.org.

This article was created as part of LDA Today, our newsletter for members including research, tips and tools for education, advocacy, and public policy information related to learning disabilities. Be sure your membership is current to receive LDA Today directly to your inbox each month!